Wikipedia and Google Translate both say that “Lignum vitae” is Latin for “tree of life”. Though no Latin scholar, I disagree; tree of life would be “Arbor vitae”. Lignum vitae is the lumber of life; lignum being the ancient Roman word for a beam or roof timber.

Confusingly, lignum vitae wood does not come from Thuja occidentalis, the arbor vitae tree. Instead it is harvested from small ironwood trees of the genus Guaiacum, which are native to the Caribbean and the northern coast of South America. Lignum vitae has been an important export crop to Europe since the beginning of the 16th century, so much so that it’s now an endangered species. The trees take three to four hundred years to mature, so it’s not particularly amenable to tree farming, especially given the long-term political instability of the regions where it is found.

Lignum vitae’s claim to lasting fame is a remarkable combination of strength, toughness, and density. The wood is so dense it sinks in water, and it’s so tough that it has been used for submerged bearings in hydro turbines in continuous operation for a hundred years. Yes, I said in continuous use as a bearing supporting a heavily loaded rotating shaft for a hundred years. Bearings made of lignum vitae were used for the rudders of great sailing ships, for the propellor shafts of steamships, for the main bearings of water-powered mills, for nearly anything you can imagine including wheelbarrows and snowblowers. Any place that bronze isn’t tough enough and steel is too likely to corrode, you’ll find a use for lignum vitae, and somebody’s probably used it. There’s just no other material like it – which is why the US Navy still uses it for jackshaft bearings in nuclear submarines, and it’s still used in huge modern hydroelectric plants. It’s been used for pulleys in steel mills, for British police batons, for cannon balls, and for gears in wooden clockworks. Only two woods have ever tested harder – South American Quebracho or “axe breaker” wood (Schinopsis spp.) and Australian Bull-Oak (Allocasuarina luehmannii) – neither of which have the workability or durability of lignum vitae.

DENSITY: 80 lbs./cu.ft.

SPECIFIC GRAVITY: 1.37

TANGENTIAL MOVEMENT: less than 1%

RADIAL MOVEMENT: less than 1%

VOLUMETRIC SHRINKAGE: less than 1%

JANKA HARDNESS: 4,500 lbf (20,000 N)

DURABILITY: Exceptional resistance to moisture, fungi and rot

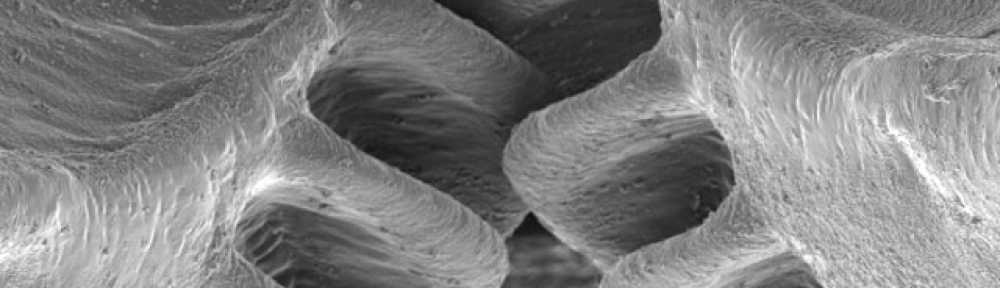

DESCRIPTION: Reddish brown when freshly cut, with pale yellow sapwood. As it oxidizes, the color turns to a deep green, often with black details. The grain is highly interlocked, making it difficult to work with edge tools, but it machines well and takes a high polish.

But it’s not just these exceptional engineering properties that make lignum vitae marvelous.

The flowers, resin, bark, and wood chips of Guaiacum trees have dozens of medicinal uses, some traditional and unverified, others well-documented in modern medicine. The resin is used for coughs, arthritis, and is a traditional West Indies pick-me-up and reputed aphrodisiac. The modern expectorant guaifenesin, (which is also used by veterinary surgeons as a horse muscle relaxant) is derived from the wood. Cellini cites it as a treatment for syphilis. Teas made from the bark and flowers have spawned more folk medicine than ginseng, and guac cards are still used for fecal blood testing. As a food additive Guaiacum has the E number of E314 and is classified as an antioxidant (insert eye roll here). Oil of guaiac is used as a soap fragrance. The list of uses just goes on indefinitely!

There are a lot of names for the various species of guaiacum. It’s called “caltrop tree” because of the foot puncturing seeds of some varieties, and the Spaniards called it palo santo or “holy wood”. If you live in an area where it can survive, you’ll find it under various names in garden centers, where its sold for its muscled trunks and pretty blue flowers. Because yes, it’s not just amazingly useful, it’s also attractive – Guaiacum Officinale, the common or true guaiacum, is the Jamaican national flower, and Guaiacum sanctum is the national tree of the Bahamas.